The Participatory Museum: Nina Simon

Over the last twenty years, audiences for museums, galleries, and performing arts institutions have decreased, and the audiences that remain are older and whiter than the overall population. Cultural institutions argue that their programs provide unique cultural and civic value, but increasingly people have turned to other sources for entertainment, learning, and dialogue. They share their artwork, music, and stories with each other on the Web. They participate in politics and volunteer in record numbers. They even read more. But they don’t attend museum exhibits and performances like they used to.

How can cultural institutions reconnect with the public and demonstrate their value and relevance in contemporary life? I believe they can do this by inviting people to actively engage as cultural participants, not passive consumers. As more people enjoy and become accustomed to participatory learning and entertainment experiences, they want to do more than just “attend” cultural events and institutions. The social Web has ushered in a dizzying set of tools and design patterns that make participation more accessible than ever. Visitors expect access to a broad spectrum of information sources and cultural perspectives. They expect the ability to respond and be taken seriously. They expect the ability to discuss, share, and remix what they consume. When people can actively participate with cultural institutions, those places become central to cultural and community life.

Community engagement is especially relevant in a world of increasing participatory opportunities on the social Web, but it is not new. Arguments for audience participation in cultural institutions trace back at least a hundred years. There are three fundamental theories underpinning this book:

1. The idea of the audience-centered institution that is as relevant, useful, and accessible as a shopping mall or train station (with thanks to John Cotton Dana, Elaine Heumann Gurian, and Stephen Weil).

2. The idea that visitors construct their own meaning from cultural experiences (with thanks to George Hein, John Falk, and Lynn Dierking).

3. The idea that users’ voices can inform and invigorate both project design and public-facing programs (with thanks to Kathleen McLean, Wendy Pollock, and the design firm IDEO).

Cultural participatory institutions, what are they?

I define a participatory cultural institution as a place where visitors can create, share, and connect with each other around content. Create means that visitors contribute their own ideas, objects, and creative expression to the institution and to each other. Share means that people discuss, take home, remix, and redistribute both what they see and what they make during their visit. Connect means that visitors socialize with other people—staff and visitors—who share their particular interests. Around content means that visitors’ conversations and creations focus on the evidence, objects, and ideas most important to the institution in question. The goal of participatory techniques is both to meet visitors’ expectations for active engagement and to do so in a way that furthers the mission and core values of the institution. Rather than delivering the same content to everyone, a participatory institution collects and shares diverse, personalized, and changing content co-produced with visitors. It invites visitors to respond and add to cultural artifacts, scientific evidence, and historical records on display. It showcases the diverse creations and opinions of nonexperts. People use the institution as meeting grounds for dialogue around the content presented. Instead of being “about” something or “for” someone, participatory institutions are created and managed “with” visitors.

The why matters!

Why would a cultural institution want to invite visitors to participate? Like all design techniques, participation is a strategy that addresses specific problems. I see participatory strategies as practical ways to enhance, not replace, traditional cultural institutions. There are five commonly-expressed forms of public dissatisfaction that participatory techniques address:

1. Cultural institutions are irrelevant to my life. By actively soliciting and responding to visitors’ ideas, stories, and creative work, cultural institutions can help audiences become personally invested in both the content and the health of the organization.

2. The institution never changes – I’ve visited once and I have no reason to return. By developing platforms in which visitors can share ideas and connect with each other in real-time, cultural institutions can offer changing experiences without incurring heavy ongoing content production costs.

3. The authoritative voice of the institution doesn’t include my view or give me context for understanding what’s presented. By presenting multiple stories and voices, cultural institutions can help audiences prioritize and understand their own view in the context of diverse perspectives.

4. The institution is not a creative place where I can express myself and contribute to history, science, and art. By inviting visitors to participate, institutions can support the interests of those who prefer to make and do rather than just watch.

5. The institution is not a comfortable social place for me to talk about ideas with friends and strangers. By designing explicit opportunities for interpersonal dialogue, cultural institutions can distinguish themselves as desirable real-world venues for discussion about important issues related to the content presented.

These five challenges are all reasons to pursue participation, whether on the scale of a single educational program or the entire visitor experience. The challenge—and the focus of this book—is how to do it. By pursuing participatory techniques that align with institutional core values, it is possible to make your institution more relevant and essential to your communities than ever before.

Design for Participation

How can cultural institutions use participatory techniques not just to give visitors a voice, but to develop experiences that are more valuable and compelling for everyone? This is not a question of intention or desire; it’s a question of design. Whether the goal is to promote dialogue or creative expression, shared learning or co-creative work, the design process starts with a simple question: which tool or technique will produce the desired participatory experience?

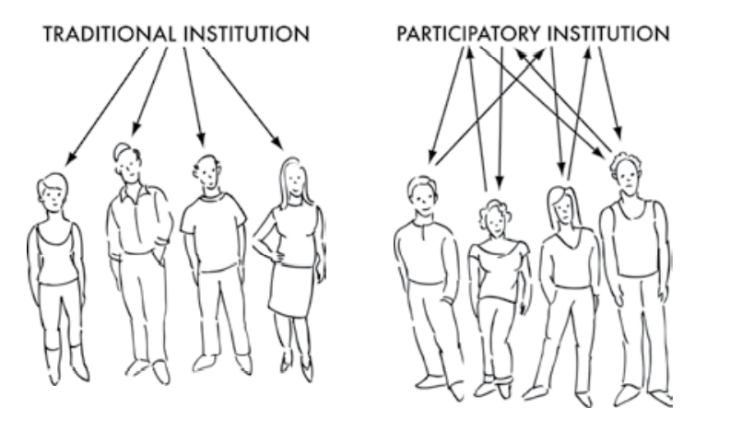

When it comes to developing participatory experiences in which visitors create, share, and connect with each other around content the same design thinking applies. The chief difference between traditional and participatory design techniques is the way that information flows between institutions and users. In traditional exhibits and programs, the institution provides content for visitors to consume. Designers focus on making the content consistent and high quality, so that every visitor, regardless of her background or interests, receives a reliably good experience. In contrast, in participatory projects, the institution supports multi[1]directional content experiences. The institution serves as a “platform” that connects different users who act as content creators, distributors, consumers, critics, and collaborators. This means the institution cannot guarantee the consistency of visitor experiences. Instead, the institution provides opportunities for diverse visitor co-produced experiences.

Supporting participation means trusting visitors’ abilities as creators, remixers, and redistributors of content. It means being open to the possibility that a project can grow and change post-launch beyond the institution’s original intent. Participatory projects make relationships among staff members, visitors, community participants, and stakeholders more fluid and equitable. They open up new ways for diverse people to express themselves and engage with institutional practice.

See more on www.participatorymuseum.org.