The Funduq in Sefrou’s Multicultural History

A fondouk or funduq, also known as a caravanserai, was built as a rest stop for travellers on often arduous journeys. These caravanserai, or traveller inns, were popular all throughout the Muslim world and can be found on well-known ancient trade routes. They provided travellers, traders and missionaries with shelter and supplies. These inns also often served as platforms for communication and exchange between diverse passers-by.

A combination depot, hostelry, emporium, artisanat, animal pen, whorehouse, and ecclesiastical benefice, the funduq was the social heart of the caravan economy. Its physical form was invariant: a narrow, two-story building constructed rectangularly around a broad open court, with a large-gated passage cut into one end and an open gallery stretched along the whole length of the second floor. A series of extremely small, airless cubicles opened off this gallery, and beneath it, along the arcade it formed on the ground floor, were ranged a number of storerooms, workshops, and countinghouses. The passing caravaners picketed their mules and donkeys in the courtyard, bolted their merchandise inside the storerooms, and slept (as noted, not usually unattended) in the second-floor cubicles. The terraces of the funduqs were used for drying animal skins and wool. Most funduqs were constructed out of earth (pisé) or brick. Most were simple, and without elaborate external decoration, although some were decorated with zelij (Islamic tilework).

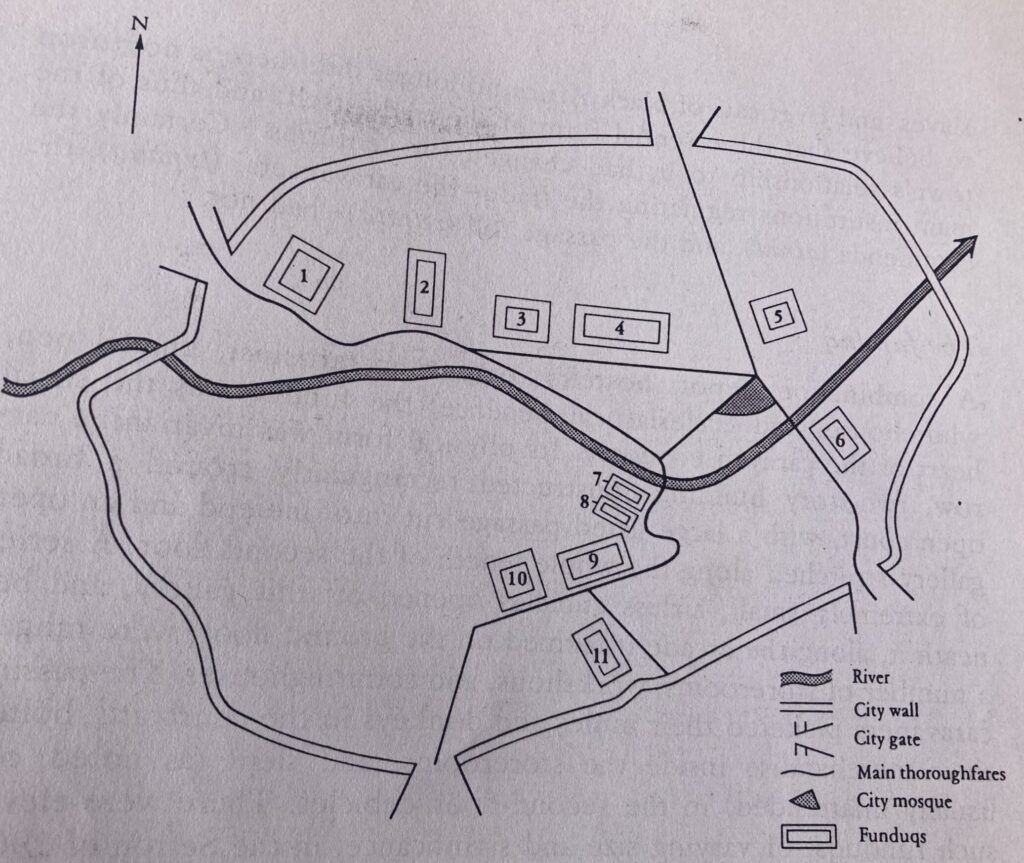

In the Sefrou of 1900, there were eleven such funduqs, of varying size and significance; and in and immediately around them virtually the whole of the city’s commercial life, then much more highly concentrated than it is now, was centered.

A more recent study of the use and purpose of nine of these Sefroui funduqs described them as follows:

Funduq Naggadi was reserved for olives and oils. It had two floors.

Funduq Zarru is now in a state of ruin. It also had two floors.

Funduq Nas Adlun is still used as a stable.

Funduq Ahl Fas was composed of two floors and 42 rooms. It hosted merchants from Fes and their wares, and it was home to weavers’ workshops and djellaba-makers. It has now been levelled to the ground.

Funduq Rhihal has been totally destroyed.

Funduq Mokhtar Djabli Slamti is now in a poor condition.

Funduq Al-Haddadine has a grand outward appearance. It is made up of a ground floor and a floor above that. It is striking for its architectural balance. The square central patio, which is 310m2, is surrounded by galleries on all four sides, which serve to hold up around thirty rooms symmetrically. The ground floor rooms are artisanal workshops, and the rooms above are all lodgings. The courtyard now serves as a place to sell and store pieces of old furniture, including doors and window frames with great decorative value.

The funduqs were not privately owned, but were, insofar as one may use the term in a Muslim context, church holdings. More exactly, they were what Moroccans call habus – properties deeded by their original owners (pious traders of the seventeenth and eighteenth, in one case apparently the sixteenth, centuries) to God’s community of believing Muslims, the umma. Entrusted to the stewardship of a religious official known as a nādir, they were auctioned by him to private merchants, usually several of them in partnership, to operate in their own way and for their own profit. The rents thus collected were then distributed by the nadir for the construction and operation of mosques, the support of Quranic education, and so on. They were, in short, pious foundations given wholly over to commercial activities themselves untrammelled by any sort of pious scruples. And, as we shall see, this curious symbiosis between the most headlong sort of merchant capitalism – business is business, and may God take pity on both of us – and the established institutions of public Islam has remained, through all sorts of detailed changes, a central characteristic of the Sefrou economy to this day.

This odd circumstance is all the more odd because, although, as Islamic law demands, the funduq holders themselves were inevitably Muslims, most of the Sefrouis involved in the funduq world – a quite restricted group in any case – were Jews. There has been an untypically large number of Jews in Sefrou for as long as we have record, and between about 1880 and 1948 (the year Israel was born), they seem consistently to have composed about 40 percent of the town’s population and 80 percent of its commercial labor force. Of the perhaps 600 or 700 men involved in the swirl of activity around the funduqs in turn-of-the-century Sefrou, not more than 100 were Muslims; the rest were Jews.

The funduq class was not however the driving force of Saharan trade. The grand merchants of Fez, seldom stirring from their countinghouses, but linked to agents in the Tafilalt (and indeed all over Morocco and into Europe) through a developed letter-of-credit system, financed and organised virtually the whole trade. Nor did the funduq class have anything to do with the transport side of things: the caravaners were pre-Saharan Berber nomads whose sheikhs assembled them into companies, found them cargoes, and then piloted them through the tangle of tribal jealousies that separated the capital from the oasis. The Sefrou involvement was mostly ancillary, limited to providing the passing services of the funduq – food, lodging, women, various sorts of craftwork (blacksmithing, saddlemaking, tinsmithing, shoemaking, weaving) – and a certain amount of petty trading of sugar, tea, and cannabis with the caravaners.

The funduq therefore played an essential role in the multicultural history of Sefrou. Trade in the age of great caravans was not only essential to the economic life of a town but also the sharing of news, goods, and beliefs. As a symbol of cultural interchange, it is fitting that our museum can be found in one of the upstairs chambers of Sefrou’s funduq el jdid (the new funduq), also known as the funduq dial ks’hb (the wood funduq). It is named as such because of its relatively recent construction, and the fact that it is home to many carpenters, who produce their goods on the ground floor.

Can you imagine the diversity of people, animals, and goods that travelled through Sefrou and stayed in a funduq? What an incredible place a funduq must have been for the sharing of stories and news across cultures!

Original source – Clifford Geertz, Suq: the bazaar economy in Sefrou.