Sufism between Fes, Sefrou and West Africa

With the fourteenth edition of the Festival de Fès de la Culture Soufie soon upon us – from 9-16 October, although it is online this time! – we focus on the spiritual links of Sufism between Morocco and sub-Saharan Africa.

Before exploring how these links were built through Sufism, let’s ask ourselves the question, what is Sufism?

Sufism is a mystical form of Islam, a school of practice that emphasizes the inward search for God and shuns materialism. It has produced some of the world’s most beloved literature, like the love poems of the 13th century Iranian jurist Rumi. Its modern-day adherents cherish tolerance and pluralism.

While it is sometimes misunderstood as a sect of Islam, it is actually a broader style of worship that transcends sects, directing followers’ attention inward. Sufi practice focuses on the renunciation of worldly things, purification of the soul and the mystical contemplation of God’s nature. Followers try to get closer to God by seeking spiritual learning known as tariqa.

The Sahara, far from being an obstacle, was in fact an important historical factor in the bringing together of people in the north and south of Africa. While the intermixing of people from Morocco and sub-Saharan Africa preceded the birth of Islam, it intensified during the Islamic era. Stemming from the Maghreb, Islam spread through the traffic on trans-Saharan trading routes, particularly between Morocco and West Africa. Some of these were the very trade routes which passed through Sefrou onto Fes, or southward to the Tafilalt. The Almoravid dynasty played an essential role in the Islamisation of sub-Saharan Africa. In the eleventh century, Almoravids emerged from the Senegal river to found an empire which consumed Al-Andalus, Morocco, and a large part of the Western Sahara. Their capital was Marrakech. The Almoravids deepened the cultural and religious links between Morocco and West Africa.

Penetration and development of Sufism in Morocco

The influence of Sufi thought in Morocco can be traced back to between the end of the eleventh century and the beginning of the twelfth through three main centres: several sufi masters who had installed themselves in Morocco, having originally come from the area of Ifriqiya under the Zirid dynasty; the influence of Al-Andalus; and the activities of Sufis who brought the doctrine back to Morocco from their travels in the East.

During the eleventh century, a form of Sufism emerged in Ifriqiya which integrated the principles of Maliki law (fiqh), and works were published diffusing Sufi doctrine. Several of the masters at the head of this new Sufi movement left Ifriqiya for the Maghreb al-Aqsa (Morocco).

By the mid-twelfth century, Sufism became an undeniable social and political reality. While Malikism remained confined to the towns and cities of Almoravid Morocco and Al-Andalus, Sufism – a rural and popular phenomenon – continued to spread into new territory under the reign of the Almohads and its influence stretched into West Africa.

It was in the twelfth century that Sufism became an essential component of the practice of Islam in Morocco. This century bore witness to the first Moroccan hagiographic works (biographies of saints), which influenced Moroccan literature up to the nineteenth century.

Moroccan hagiographic works mention several black saints, probably of sub-Saharan African origin. It is notable that of the 277 Moroccan saints listed by Ibn al-Zayyât al-Tâdilî in the twelfth century, 31 are of West African descent. The most illustrious of these are: Abû Yazâ, the great saint of the Atlas; Rayhan al-Aswad (‘the Black’) one of the greatest saints of the rich city of Ceuta; Abû Shuayb, great saint of Azemmour, and Abû Jabal of Fes (one of the most celebrated saints in the Maghreb).

Golden era of relations between Morocco and sub-Saharan Africa

Cultural and religious relations between Morocco and sub-Saharan Africa flourished most strongly in the fourteenth century, which corresponded to the height of the hugely influential Empire of Mali, and the reign of the Merinids in Morocco. The links between these two empires involved exchanges of ambassadors and the transferral of students to the madrasas of Fes and Marrakech.

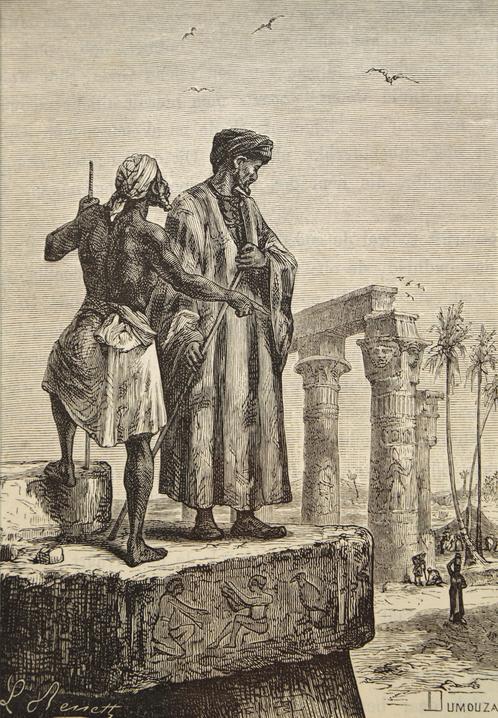

Under the reign of the Merinid sultan Abû Inân Fâris, the traveller-explorer Ibn Battûta undertook his famous voyage to Mali (June 1352 – October 1353). During this trip, Ibn Battûta found communities of Moroccans in each urban centre he visited.

Throughout the Middle Ages, following the example of Ibn Battûta or Leo Africanus, merchants and religious men crossed the Sahara and installed themselves in the urban centres of West Africa. From the thirteenth century, the Moroccan preachers and merchants who frequented Africa were mostly Shadhili Sufis. By the mid-fifteenth century, Moroccan saints were both traders and royal secretaries. They played an important role in the expansion of Islam under the Malikite rite.

The Moroccan conquest of Songhai in 1591 consecrated cultural relations between Morocco and West Africa. In consequence, familial links with Morocco began to sprout between the two regions as Moroccan soldiers started families with women from Songhai.

During his exile in Morocco, Ahmed Bâba of Timbuktu (1566-1627) had a major influence on Moroccan Islamic culture. Through his teaching at Jâma al Shurafâ, in Marrakech, he reinforced the cultural links between Morocco and West Africa. The works of this great writer continue to enrich Moroccan libraries.

Confraternities and zawiya

The creation of confraternities and zâwiya was new to Moroccan Sufism in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. The Sufi movement concentrated on education and moral reform, and became a political program fighting against colonial domination. Sufi masters were invested in an almost prophetic mission, becomes central personae around which resistance to foreign occupation formed. A multitude of confraternities, of which several were branches of Shâdhiliyya, organised around the same model and played a leading role in the religious life of the Maghreb and West Africa. The Mouridiyya confraternity, one of the largest in Senegal, is the cradle of a Sufi Islam with diverse confluences and ancestral links with the Sufi schools of Morocco. Widely influential, Mouridiyya was only supplanted by the tarîqa, Tijâniyya.

The tarîqa Tijâniyya is named after its founder, Cheikh Ahmed al Tijâni, who was born in 1737 at Aïn al-Mahdi in Algeria, and lived in Fes. On occasion of his death in 1815, the tarîqa begun to conquer the south of Morocco, then Senegal and sub-Saharan Africa. Despite differences in religious practices, all of Senegal’s Tijâniyya zawiya had in common with Morocco the search for a direct line of spiritual descent. Fes, which is home to the mausoleum of the founder of the zawiya Tijâniyya, is a mythical place where all Tijâniyya followers dream of praying at least once in their lifetime.

Due to its position just outside of Fes on the trans-Saharan trade route going south to sub-Saharan Africa, the spread of Sufism passed through and influenced Sefrou, too. One Tijâniyya confraternity can be found in the Mellah. It is still open, meeting on Fridays between 2 and 4pm for chanting recitals.