Trade and Turn-of-the-century Sefrou

Though Sefrou is today essentially a regional market, a place where half-commercialized tribesmen meet super-commercialized shopkeepers on free if somewhat less than equal ground, it has not always been thus. Prior to the Protectorate (and especially prior to the French incursion into the Algerian Sahara around the turn of the twentieth century), the town’s role in short-distance trade was distinctly secondary to its role in long-distance trade. It was out of the caravan traffic – south toward the Sahara and sub-saharan Africa and north toward the Mediterranean and Latin Europe – that the Sefrou bazaar arose. For about the first millennium (900-1900) of its existence, the town was less a hub than a way station, a link between remote economies rather than a focus for adjacent ones. Its function was to connect.

Probably the most important of such connections was that between Fez, then the political and cultural as well as commercial capital of the country, and the Tafilalt, the great desert port of southeastern Morocco. The first stopover (and the last town) on the way out, and the last stopover (and the first town) on the way in, Sefrou was both the jumping-off place and the landfall of this trade – the passage gate to 480 kilometres of winding mule trail, as accidented politically as it was physically.

This trail, the famous trīq s-sultān (‘The Royal Way’, so-called because it linked the dynasty’s capital with its ancestral shine) ran from Fez across the Sais Plain into Sefrou, from which it climbed up into the Middle Atlas, then down to cross the blank Mulwiya Plateau, then up again, this time to 2,000 metres, through the High Atlas, finally descending into the palm groves and camel tracts of the north Sahara – an eleven or twelve-day trek. Little circumstantial can be said about Sefrou’s involvement in the trade that passed along this route prior to 1900. Except for the fact that the volume of trade was not what it must have been and that, by 1900, European guns and cottons were beginning to appear in it, though amber, slaves and civet cats of sub-Saharan Africa no longer did, there is no reason to believe that the essential form of the trade itself, and thus of the town’s relationship to it, had changed for centuries. Certainly the main institutions regulating the trade – the caravanserai (funduq), the commenda (qirād), and the passage toll (zettata) – had not.

The story of Mulay Ali, Qaid Umar and the Jewish qirad-givers

There was a handful of men – around 1900, perhaps a dozen Muslims and twice that many Jews – who contrived to buy into the caravan trade, and become what Moroccans call, still today with a touch of awe, tājir. By using the qīrad, they laid the real foundations of the bazaar economy and turned the town from a mere service station or doorsill to Fez into a commercial centre, minor but vigorous, in its own right.

The qīrad is part loan, part partnership. Sefrouis still refer to it, as they do to almost any persisting commercial relationship, as a ‘partnership’ (šerka). The supplier of capital provides money or goods to a trader, who then trades on his own, in his own way, and without answering to anyone but himself. If there is a profit, the investor shares in it in some preagreed proportion; if there is not, then not, and no debt remains to haunt the relationship.

In turn-of-the-century Sefrou, the few merchants with resources enough to launch qirad arrangements were mostly Jews. They made the arrangements with both Muslims and Jews, but the latter formed the core of their operations.

There was a large Jewish community, at least as ancient as Sefrou’s, in the Tafilalt, and small knots of Jews, also originating mainly from the Tafilalt, could be found huddled around most of the camp stops along the route, doing a little selling here, a little buying there. The urban magārba (northern town-dwelling) Jews of Sefrou and the filālī (rural of the south and east) Jews of Tafilalt built extensive and usually highly stable investor-agent qirad relationships. It was across this city Jew – country Jew synapse of class that the shopkeeper and artisan world of the permanent bazaar was first linked with the shepherd and traveling-man world of the periodic bazaar. Beside these Jews, the Berber qaid, Umar al-Yusi Buhadiwi, and the šerīf munitions maker, Mulay Ali b-l-Hashimi Bu Bnitat l-Alawi, were the greatest buyers into the passing caravan traffic.

Mulay Ali was a classic urban type. He was a šerīf, a descendant of Mohammed. He was also an Alawi sherif, which meant he was, in theory anyway, a distant relative of the sultan and the closest thing to a local patrician that Sefrou had to offer.

His Alawi ancestors had come to Sefrou from the Tafilalt, probably shortly after the dynasty’s capture of Fez in 1667, and his contacts with the large Alawi community (several thousand people) still trading there at the end of the nineteenth century provided the social foundation for his activities. The economic foundation lay in the gun trade – after the 1890s, a very rapidly expanding affair. In one of Sefrou’s funduq, for which his father, and then he, had held the lease, Mulay Ali organized a fair-sized craft industry, some twelve or fifteen workers, in ammunition manufacture. These workers stuffed cartridges among other tasks. This industry proved immensely profitable and gave Mulay Ali a monopoly hold on the local traffic.

Qaid Umar al-Yusi Buhadiwi was the dominant political figure in Sefrou town and countryside between 1894 and 1904. He, his family and his entourage were the only Berbers living inside the town at that time. He was neither a merchant nor literate, so he operated through two or three Sefrou Jews as his personal agents. Qaid Umar grew jealous of the growing power of Mulay Ali and the emerging class of Jewish funduq entrepreneurs, so he persuaded the sultan to remove Mulay Ali from the arms trade. The workers were imprisoned and the funduq ransacked; Mulay Ali escaped, as such men will, with a ransom.

By then Mulay Ali had built up an extensive network of qirad relations with Tafilalt sherifs and other traders, Muslim and Jewish alike. He had become a large-scale operator – almost of Fez proportions – in the tea, sugar, wool, cloth, and olive trades. With four secretaries, all Sefroui muslims, his funduq was the most substantial commercial institution in the town until about 1915, when the caravan trade stopped forever. The funduq had become what Moroccans call a ‘commodity house’ (dar s-sila), a domicile of trade in itself. All this meant that Mulay Ali probably did not regret too much his enforced disentanglement from the arms business (which moreover had its risks).

By the turn of the century, almost all the funduq lessees were qirad givers, some of them on a large scale, and their funduqs had become commodity houses too, each specialized in one or another trade. Relating to the map above, Funduq number 6, headed by a pair of wealthy Meccan pilgrims, one of whom would become the dominant political figure in Sefrou after Qaid Umar’s death, was the centre of the grain trade. The wool and lumber trades, separated in different parts of the building, were concentrated in number 11, whose director was an Alawi. A third Alawi, again unrelated, leased number 9 in partnership with an Arab-speaking migrant from northwest Morocco, the so-called Jbala, and made it the focus of Sefrou’s hide and leather trade. The tea and sugar trade was centred in Mulay Ali’s funduq, number 4, after its munitions days were over; the cloth-trade in the Fez-launched one, number 2; the olive and olive-oil trade, under two wealthy local farmers in number 7.

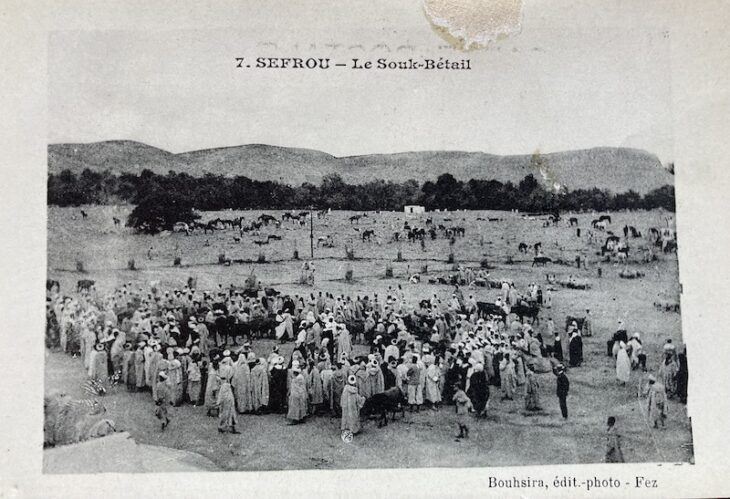

All sorts of people – financiers, traders, millers, weavers, tanners, blacksmiths, shoemakers, caravaners, Jews, Arabs, Berbers – crowded in and around these mini-emporiums. Shops, ateliers, and even small ad-hoc in-the-street markets in old clothes, bread, vegetables, mats sprang up around them. Mule stops transformed into markets, they provided the nucleus around which the developed region-focused bazaar economy that emerged in the 1920s crystallized.

Keywords from this article: qirād, trīq s-sultān, tājir, šerīf.