The Origins of Sefrou: the Speech of Si Bekkaï

Below is a long extract from a speech given on 30 April 1950 at the Riad Caïd Omar, by the influential Si Bekkaï, pacha of Sefrou from 1944 to 1953. In 1953, Si Bekkaï was one of the few pashas throughout Morocco to sign a declaration condemning the deposition of Sultan Mohammed V by the French, whereby he stood down from his post. Within this declaration, he claimed: ‘Je ne peux, en effet, servir un régime que je tiens pour illégal’. He would later become prime minister of Morocco under Mohammed V between 1955 and 1958. Far away from these high political stakes, in this speech Si Bekkaï spoke on the history and origins of his home-town, Sefrou.

Unfortunately, there is nothing clear-cut about the true origins of Sefrou. However, it must be acknowledged that all our sources reflect – more or less – the oral tradition and that they only date it to the reign of Moulay Idriss II, i.e. around the year 800 (2nd century of the Hegira). The great Arab historian, El-Quitass, himself mentions Sefrou in his book “The exploits of Moulay Idriss”, only insofar as the latter city had been Islamised by the founder of Fez.

Before 682 this small centre was already called Sfro. We are at the time of the pagan natives whose exact origins are not well known. All we know is that these Berbers were without religion, lived rustically and were, at least superficially, influenced by the Phoenicians, Romans and Byzantines.

Some people claim that the word Sfro, according to the local pronunciation, comes from the Arabic verb Safaro. However, given what we have just demonstrated, namely that the name Sfro already existed before the introduction of the Arabic language in this country, and that the verb in question does not initially bear a letter çad, a cedilla in French, but an Arabic S, we are logically inclined to reject this.

Divided by three large and parallel mountain ranges, northern Morocco has always been more flourishing than its southern part. As these mountains have never been impassable ramparts, it is certain that emigration has always taken place in a south-north and slightly south-east direction, following the valley of the Moulouya. There were several reasons for this emigration: I will mention only the poverty of the Saharan territories, due to drought, the fleeing of clan battles and the trading caravans that came north to do business. In this back-and-forth movement, access to water points dictated journey routes. The river at Sfro seems to have been the last one to the north.

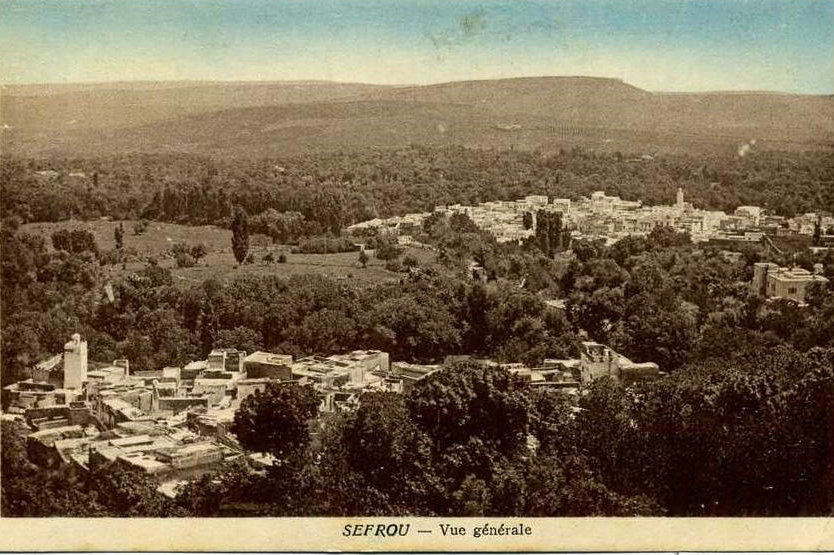

An oasis without palm trees, but a nest of greenery resting on a rich soil fertilized by the waters of the Aggaï river, it was the best terrestrial paradise for people tired of all kinds of privations.

Around the year 700, the “troglodytes” lived on the slopes of Immouzer du Kandar, Bahlil and Mezdra Jorf, around the Aggaï river, near its mouth. Little by little these troglodytes came out of their caves and sheltered in noualas or khaïmas made of goatskin while waiting to build. Then, with the means at hand, houses were built; the surrounding forests provided the cedar; at the time these forests were flourishing, they had not yet suffered the devastation of the Hilalians. They had no forest guards, they only had to be guarded against lions, tigers, panthers and other wild beasts.

From house to house, the ksours were formed in three groups which are:

1- the Ksours El Fouqanynes (upper)

2- the Ksours El Ouastanynes (in the centre)

3- the Ksours Ettchtanynes (lower)

The Ksours El Fouqanynes would have been 17 in number, spread along the banks of the Aggaï river, from its source to the present-day town of Sefrou.

The Ksours El Ouastanynes occupied more or less the same location as modern-day Sefrou. There were 10 of them.

At the border of the Ksours El Ouastanynes, the river Aggaï was called river Sfro; near Tofr it was called oued El Ihoudi (river of the Jew). The Jews who came from Tafilalet, from the south of Algeria and from Debdou, placed themselves under the protection of the Ksourians who settled them in the Ksar, called Tofr and Ksar El Koufar (of the miscreants). These Jews were attracted by trade and made a home with the Ksourians. There were large numbers of them. They grew in parallel and in proportion to the Ksourians and form a good third of the current population of Sefrou.

The Ettchtanynes Ksours were 15 in number; they were spread out along the Sfro river, up to its confluence with the Sebou.

Incohesive and poorly guarded against the raids of the neighbouring mountain people, these new Ksourians, half-settled, nevertheless began to work the land. They made it yield cereals, planted olive trees and already produced “beldi” turnips and carrots. The women worked the wool. The Ghzel souk was well stocked. The primitive scales used for weighing wool were hung from a strong olive branch. But these Ksourians were easy prey and very tempting to the warriors of the surrounding tribes. As a result they were constantly pillaged. To defend themselves better, they had to close in on each other. It is surely this reason of self-defence which obliged the Ksours El Fouqanynes and Ettchtanynes to regroup around the Ouastanynes to make the current city of Sefrou.

The Jews were not forgotten in this, since they were placed in the heart of the agglomeration in order to better protect them against the raids coming from outside. A quick glance at the present Mellah, where it is not uncommon to find three-storey houses and sometimes more, proves that the Jews were also the victims of their own protection. As they were unable to expand in width, because they were well surrounded by the Ksourians, their dwellings inevitably grew in height.

As we have just seen, these Ksours already formed a very compact agglomeration, but did not yet have ramparts. In the absence of guard walls, the Sefriouis used as much as possible natural obstacles and high reed baskets full of earth, lined up next to each other – these baskets are used nowadays to store barley, wheat and corn.

Before founding Fez in 808 (193 of the Hegira) Moulay Idriss II stayed for two years in Sefrou. This great monarch settled in the Habouna district, which he very quickly converted to Muslim doctrine. It is because of the eagerness of this district to embrace Islam that Moulay Idriss said of its inhabitants “Habouna”, which means “who loved us”. The other fractions of the city simply followed the example of Habouna in Islamisation according to El Qirtass.

But according to one oral legend, whose author(s) are not mentioned, Moulay Idriss would have encountered more difficulties in convincing the Maghraoua fraction with Sheikh Messaoud El Maghraoui. This sheikh, who persisted in his refusal to rally to Moulay Idriss, was condemned to be sawn between two boards. This torture would have taken place in public.

The death of Sheikh Messaoud would have resulted in the flight of a good part of the Maghraoua to the Beni Alaham of El Ader where they would still have descendants, to the Beni Snassen, and finally to Taza and Guercif.

Still according to the oral tradition, there is another theory for the flight of the Maghraoua. Once again I pass the floor to oral stories:

“It is in the Merinid period that the following legend is situated: to reinforce their authority the Merinids sent in each kaskah 4 or 5 moghaznis, who were maintained by the population. In turn, each house hosted them and offered them a large diffa. They were once the guests of a notable from the Ahel Sefrou. A series of tajines had been served and when the tajine of roasted chickens was presented, the moghaznis noticed that a chicken was missing a leg and asked the cause of this offence to their dignity. The master of the house replied that the leg had been given by himself to his little child who was crying for a piece of chicken. The moghaznis having demanded that the child be presented to them, one of them, a Herculean brute, seized it, threw it to the ground and, placing his foot on the trunk of the toddler, seized it by the leg and pulling it abruptly separated it from the body of the child, as if one were tearing the leg off a chicken. The child died on the spot. Despite the indescribable pain of the unfortunate parents, the Sultan’s envoys quietly continued their feast without showing the slightest embarrassment or regret for what had happened.

As soon as they left, the child’s father had all the notables of the surrounding ksours invited to his house, letting them believe that he was offering a diffa on the occasion of his son’s circumcision. As soon as all the notables had gathered, the father placed a large table in their midst, carrying a dish covered with a rich veil, and asked them to come forward around the table to honour his meal.

The most venerable of the elders removed the veil and a dreadful sight presented itself before their eyes: the dead child with its leg separated from its body. The inconsolable father then wept as he recounted the scene of the horrible tragedy and demanded vengeance.

The notables, terrified and disgusted by this unprecedented crime, decided to massacre all the moghaznis of the Aggaï river. The next day, all the representatives of the Sultan were murdered by the people of the valley who fled with their families.”

If I had to comment on the two legends we have just mentioned, I would personally trust the first, because the second seems to me to be a bit inflated, but let’s return to Moulay Idriss.

During his stay in Sefrou, Moulay Idriss made a few trips to Bahlil and converted the inhabitants to the Muslim religion. Still according to El-Qirtass, Bahlil did not resist the Mohammedan conversion either. But it seems from oral tradition that the Chkounda fraction only resigned itself under duress to the apostolic action of Moulay Idriss, as it was probably still influenced by the ideas of the Second Roman Legion, from which the name Chkounda comes.

In any case, the people of this fraction gave a very bad reception to the Idrissite Sultan. It is following a failure in Bahlil that Moulay Idriss is said to have said from the Jbel Binna, on his way back to Sfro: “Hadha Binna or Binhoum”, which literally means: this is between us and them. Since then, the name Binna has remained for this mountain that you see on the right when you arrive in the oasis.

Without water and obliged to go to the Aggaï river for supplies, at the risk of ever-increasing dangers, the Bahloulis finally promised Moulay Idriss to submit to his will on condition that he would provide them with the vital and ever-precious liquid that is water. Moulay Idriss granted their wish: he returned to their home and performed a divine miracle by making water gush out of the ground after having struck it with his sword. This water would be the source of Aïn Rta which is nowadays in the middle of the village. In admiration for this divine miracle, the last hostile Bahlulis immediately rallied to the Monarch, but not without having earned the nickname of Bahlil, which was given to them by their neighbours who mocked them for having hesitated so much to embrace Islam.

Apart from the tomb of Sidi Nadjar, the standard-bearer of Moulay Idriss, which can still be found near a large ash tree, whose trunk is enormous in front of the Hôtel de la Frènaie, there is no concrete trace of this great Idrissite Sheriff. The end of Moulay Idriss’s stay in Sefrou would be marked by his famous sentence, of which the Sefriouis are still very proud, at the expense of their Fassis brothers: “I am going from the city of Sefrou to the village of Fez”.

See original article, in French, at http://adafes.com/download/down/Historique%20de%20Sefrou%20par%20Si%20Bekkai%A8.pdf